On 11 March, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the COVID-19 virus outbreak as a pandemic due to the exponential increase in the number of cases in more than 100 countries. Then on 16 March, President Duterte placed the entire Philippines under a “State of Calamity” amid the threats posed by COVID-19. Since then, the Philippines has been battling the spread of COVID-19, coupled with the surmountable challenge of addressing the most basic health and socio-economic needs of the people.

Almost all efforts and resources are geared toward saving lives and mitigating the socio-economic effects of the deadly coronavirus with physical well-being taking priority over mental health needs.

Most often than not, the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of people gets little attention or is put on the back burner, which has far more long-term effects and consequences. In this regard, it is thought-provoking to look at the impacts of the pandemic on the mental health of Filipinos, the general mental health situation in the Philippines, and the various existing interventions available to address mental health-related concerns.

Mental health is defined by the WHO as “a state of well-being in which an individual realises his or her abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and can make a contribution to his or her community.”

Mental Health Situation

The WHO reported that even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Philippines had already one of the highest rates of depression in Southeast Asia, affecting more than three million Filipinos. Though there is no consolidated epidemiological data and statistics on the state of affairs of mental health in the Philippines, there is information that will provide an idea as to the state of the mental health condition of the country. For instance, 14 percent or 1.4 million Filipinos with disabilities were identified to have a mental disorder (Philippines Statistics Authority, 2010).

The National Statistics Office identified that mental illness is the third most prevalent form of morbidity in the country. There are around 88 cases of mental health problems for every 100,000 Filipinos (Department of Health (DOH), 2005). Nonetheless, in the advent of a pandemic, this is an understatement of the true extent of the mental health problem in the country.

Furthermore, based on a 2004 WHO study, up to 60 percent of people attending primary care clinics daily in the Philippines are estimated to have one or more “mental neurological and substance” (MNS) disorders. The 2000 Census of Population and Housing showed that mental illness and mental retardation rank 3rd and 4th respectively, among the types of disabilities in the country (88/100,000). The 2011 WHO Global School-Based Health Survey revealed that in the Philippines, 16 percent of students between the ages of 13-15 have seriously considered attempting suicide, while 13 percent have attempted suicide one or more times during the past year. Intentional “self-harm” is the 9th leading cause of death among 20-24-year olds (DOH, 2003).

Likewise, a study conducted among government employees in Metro Manila revealed that 32 percent out of 327 respondents have experienced a mental health problem in their lifetime (DOH, 2006). And based on 2015 Global Epidemiology on Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry, and the 2013 7th edition of Kaufman’s Clinical Neurology for Psychiatrists study, cases of schizophrenia accounts for a million of the total population, bipolar around a million as well, major depressive disorder around 17 million, while dementia among those 65-years and older accounts for around five percent of the population.

The above-mentioned statistics show that mental health-related concerns/disorders in the Philippines have been around even before the advent of the novel coronavirus. The National Center for Mental Health (NCMH) reported a spike in the number of Filipinos facing mental health issues due to the pandemic, receiving an average of 30 to 35 calls daily from March to May 2020 compared to 13 to 15 calls daily from May 2019 to February 2020.

The monthly calls received and tabulated by the NCMH averaged 953 calls from March to May 2020. This is markedly higher than the 400 monthly average calls from May 2019 to February 2020 or before the pandemic hit the Philippines. According to the NCMH, the monthly average calls related to suicide also increased to 45 calls per month as of 31 May, 2020.

COVID-19 Impact On Mental Health

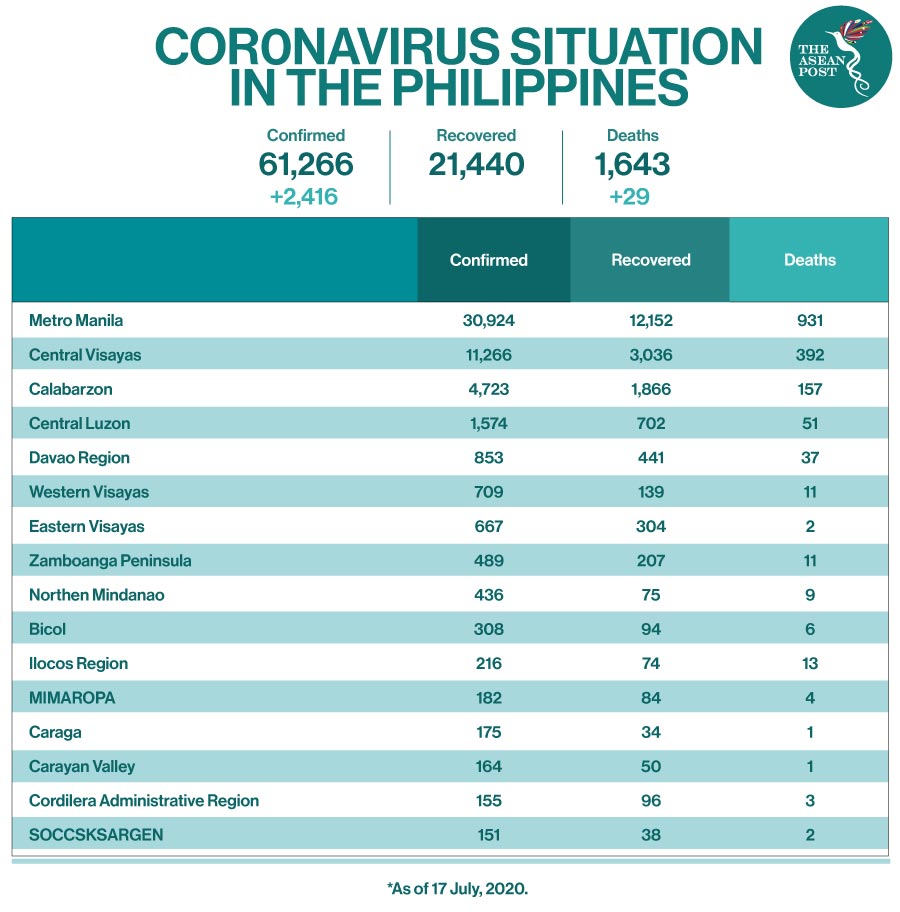

Facing the reality that there’s no vaccine available yet to prevent the continuous spread of the novel coronavirus, coupled with the still increasing number of positive cases, and not knowing when exactly the virus will be defeated is a daunting prospect for many. Thinking of whether life will ever return to normal, and how one will survive amid the pandemic, are some of the questions making ordinary Filipinos very anxious.

Likewise, questions like how will one survive economically and financially amid a pandemic; the sudden changes in everyday life and how to cope with them; the unremitting fear of being infected, the fear of dying from the virus, or the fear that a family member or relative might be infected with COVID-19 and die, and the fear of not being able to receive medical treatment in time are also playing on the minds of many Filipinos.

The daily flood of news and information about COVID-19, classifying and deciphering which ones are real/authentic and which are fake, convoyed with the daily newsreels on the rising numbers of positive cases, hospitalisations and reports of deaths around the world and in the Philippines, are just some of the topmost daily concerns among ordinary Filipinos, as they struggle against the novel coronavirus. All these questions, worries and stress added on top of the daily grind of life, compounds the mental burden of people.

Simply not knowing what will happen in the coming days has added to the anxiety of every Filipino amid the pandemic. Furthermore, adapting to new realities like working from home, temporary unemployment, home-schooling of children, and lack of physical contact with other family members, relatives, friends, colleagues at work, and the huge change in the daily routine of adapting to the “new normal”, when taken as a whole, affects the mental health of every Filipino in general.

Interventions

Given the toll on the mental health and well-being that the pandemic has brought upon ordinary Filipinos, access to mental health care, including essential continuing care, and the provision of psychosocial support services, must be accessible and made available to all Filipinos free of charge. President Duterte in 2018, signed the Republic Act (RA) 11036 also known as the “Mental Health Act,” that aims to establish a national mental health policy underscoring the basic rights of all Filipinos to mental health. The law also aims to enhance the delivery of integrated mental services, promoting and protecting the rights of every Filipino to access mental health services and facilities.

However, even after the passage of RA 11036, mental health in the country is still poorly financed. Around just three to five percent of the total health budget is spent on mental health (WHO & DOH, 2006). In terms of mental health practitioners/staff, the ratio of doctor to patient is more or less 1:80,000 Filipinos (WHO & DOH, 2012). To date, there are only around 600 psychiatrists in the country and around 400 of them are based in the National Capital Region (NCR).

This ratio is lower than in other Western Pacific Rim countries with similar economic status (WHO, 2014). The WHO’s recommended global target is 10 psychiatrists per 100 000 population. Also, most of the mental health practitioners in the Philippines work for private health institutions, and others are in private practices mainly based in metropolitan areas like the NCR.

The NCHM has responded to the challenges posed by the pandemic through the establishment of its toll-free crisis hotline for the public as an add-on to the other mental health programs that it is already running. The private sector and some non-government organisations (NGOs) are also providing psychosocial services to Filipinos who require these kinds of services via tele-healthcare.

For instance, the Philippine Mental Health Association Inc., (PMHA) offers community-based mental health programs and extends help through online “mental health and psychosocial support” to front liners, COVID-19 patients and survivors, Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) repatriates, and vulnerable groups like the elderly for free since 11 May. For the elderly who have anxieties about their physical health, the Barangay Health Emergency Response Team (BHERT) of local government units (LGUs) is also quite helpful to some extent.

Conclusion

Mental health is indeed a concern that is real and serious especially in this time of a pandemic. This concern should not only be responsibility of the government but of the whole community. It is therefore critical for mental health concerns and issues to be given additional attention and more space in the national strategy and response to COVID-19 by the national government, especially in the recovery phase.

Health care programs and systems especially those that pertain to the need for mental health interventions should be mobilised in a timely manner. Psychosocial services must be made available to all Filipinos who require these services for free as much as possible. Also, the importance of culturally sensitive mental health interventions should be given due course and importance.

There should also be more efforts on the part of the DOH and its affiliate agencies like the NCHM to systematically and scientifically assess the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of Filipinos, more particularly on vulnerable populations like the elderly, children, adolescents, those who were already diagnosed with mental health concerns, and those belonging to lower socio-economic classes, especially in rural and remote areas who barely have access to mental health-related services and mental health practitioners.

While President Duterte and policymakers are pressed to exercise strong political will to make hard choices concerning the reopening of the Philippine economy while trying to address the still-rising number of COVID-19 infections, Filipinos should turn to each other for comfort, consolation, cooperation, and unity.

It is the compassion, understanding, level-headedness, commitment, and self-discipline of every Filipino, and simply looking out for each other that will make a difference in the continuing fight against the novel coronavirus in the days to come. Ultimately, Filipinos must come to realise that the battle against COVID-19 is not just the responsibility of the Philippine government alone but of every Filipino. All Filipinos are in this together and must fight as one to defeat this unprecedented scourge.

Source: The ASEAN Post

https://theaseanpost.com/article/covid-19-impact-mental-health-filipinos