The current state of global politics and world order necessitates “Regional Integration” as a viable alternative governance framework or instrument in facilitating and promoting peace, security, and the promise of growth and development for some geographically linked countries that agree to form a regional body. This is exemplified by the European Union (EU), which is said to be the most advanced and successful regional integration the world has ever seen. Conversely, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is currently preparing to be more politically, socially, and economically integrated towards an ASEAN Community starting next year (2015). Without a doubt, “regional integration” has become a global phenomenon of growing relevance. The proliferation of “region-building” has become a sustained feature of global political, economic, social, and cultural realities. Many have said that the impetus behind “regional integration” is the idea that it is accordingly an alternative solution to the inability of nation-states to deal with common issues through large multi-lateral frameworks.

ASEAN is one of the most promising regional inter-governmental bodies that to some degree is following the example of the European Union. ASEAN as a regional body thus far is composed of ten (10) Southeast Asian countries namely the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Brunei, and Myanmar. It was founded thru the ASEAN Declaration (Bangkok Declaration) in August 1967. Two (2) of the crucial rationales behind the creation of ASEAN are to facilitate peace among the countries of Southeast Asia (SEA), and economics, – that is to evolve a more intertwined and tight economic cooperation among the member-countries.

Conceived in November 2003, the fulfillment of the objectives of the ASEAN Community 2020 has been accelerated to be met in 2015. Such a move is a historic and landmark experience in the evolution of ASEAN as a regional body. It is a vision that embodies the philosophy and framework of regional integration. ASEAN Community 2015 was adopted during the Declaration of ASEAN Concord II (Bali Concord II) in October 2003 in Bali, Indonesia. It envisions an ASEAN community that stands on three pillars namely; political- security, economic and socio-cultural all to ensure a wave of lasting peace, political stability, and shared economic prosperity and growth among the member states.

Following the footsteps of the European Union (EU), ASEAN member states acknowledge the fact that the making of ASEAN Community 2015 must build on fast track implementation of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) blueprint. It aims to transmute ASEAN into a region where there is a free flow of goods, services, labor, investments, and capital through economic liberalization. It wants to create a region that is open, outward-looking, inclusive, and most of all market-driven, with the institutionalization of a single-market economy with a production base that is highly competitive and fully integrated into the global market. All these will lay the ground for a greater opportunity that should result in great economic growth, and consequently raising the standard of living of ASEAN citizens. In terms of trade and investment, AEC promises a wider and numerous varieties of goods and services to choose from through the enhanced intra-trade activities among ASEAN member states. This facilitates immense demands for goods and services in various industries such as the manufacturing industries, transport, logistics, communication, and the like. These should create employment, more entrepreneurship, novelty goods, and services, which are all beneficial to ASEAN consumers. Furthermore, AEC will accordingly usher in a more vibrant business networking across ASEAN, and beyond. This is expected to contribute more to economic development and prosperity bringing more investments intra and extra regionally speaking.

However, given all these promising benefits that AEC is posing, there are caveats and serious issues that need utmost and proper attention. First and foremost, it has to create mechanisms on how it could absorb the shockwaves that AEC may bring to countries in ASEAN that are not ready and competitive enough to participate in a liberalized regional economy. This is something serious because more than half of ASEAN member states are not prepared substantially to participate in a market-driven regional economy Liberalized economies would entail economic restructuring which most often than not leads to such negative effects as labor retrenchment, the elimination of local small scales businesses by huge multi-lateral corporations, and migration from less competitive countries to more competitive ones thereby creating “brain drain”. These are just a few of the many possible shockwaves that a fully liberalized regional ASEAN Community 2015 might bring to the region given the varied and uneven economic standing of ASEAN member states. Whether we like it or not, it is glaringly apparent that the “playing field” is not at all equal for all countries in ASEAN. This condition may create irreversible adverse consequences especially among less efficient and less competitive economies in ASEAN. And because of all these, AEC instead of delivering its promises of economic prosperity, development, and higher economic growth, might deliver otherwise. Nonetheless, despite the limited time there is for ASEAN economies to prepare for all these possible negative repercussions that AEC may bring, there is no turning back. ASEAN Community 2015 is fast approaching and whether ASEAN member states are ready or not, the show will go on whatever the results maybe.

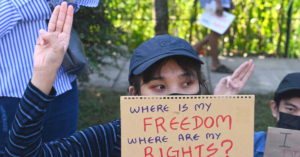

The next equally important pillar in the realization of ASEAN Community 2015 is the ASEAN Political-Security Community (APSC), which aims to create a region that is democratic, secured, and respects human rights and the rule of law. Furthermore, when you talk about security concerns, it envisages a regional community of countries that peacefully coexist, free as much as possible from inter and intra-state conflicts, living in a resilient and cohesive region vis-à-vis a more volatile geopolitical order.

As far as the implementation of APSC’s goals and objectives is concerned, one could say that it’s mixed of challenges and milestones for ASEAN. Though it has been argued by many that APSC progression towards the realization of its aims seems to be very slow, and most difficult compared to the other two pillars, still, we cannot deny the fact that it had its relative successes in terms of political development. One concrete example would be the agreement among ASEAN member states to uphold and commit themselves to the promotion and protection of human rights and democratic values and ideals, something unimaginable decades ago. But now, at least, ASEAN member states came into an understanding that this is something they need to deal with. However, this political development has to be taken with a grain of salt precisely because ASEAN is still, in relative terms, way behind in making concrete realities its human rights and democratic commitments. Many of the member countries lack the political will to implement mechanisms and procedures to protect human rights and create a culture of democracy in their respective states, where people can substantially enjoy their fundamental freedoms while upholding the rule of law. This is still a very challenging situation for ASEAN as it moves towards its goal of having a politically secured ASEAN community. In any case, while ASEAN remains a region where human rights violations are somewhat gross, the fact is that the normative principles and prescriptions in the promotion and protection of human rights and democracy had already been set in the ASEAN Charter, and are actually in the process of mainstreaming, albeit these are yet to be experienced substantially in concrete terms. At best, this is already something that could be attributed as promising.

On the political security side of ASEAN cooperation, while it gained some relative success in the overall schemes of things, it remains very problematic with a lot of challenges to contend with. APSC approach towards security is still very much traditional in the sense that it is very much within the context of “state-centrism”, and is fixated with inter-state security dynamics. It centers on traditional security issues such as wars, the proliferation of nuclear weapons, disarmament, and the like. It fails to incorporate “human security” as a vital aspect of creating a more people-centered framework for a secured ASEAN community. Emphasizing human security simply means placing “peoples” – their needs want, and rights – at the heart of the security agenda, as against that of “state security”, which is predicated on the pretext that ASEAN states are relatively repressive in their ways of governing. This statist emphasis, in most cases, goes side by side with failure to provide for people’s basic needs and wants, more so securing their rights and fundamental freedoms. This glaring reality is one of the most difficult tailbacks that ASEAN needs to face and grip if it seriously wants to create an ASEAN that is politically secured in 2015. Even so, political security cooperation under the APSC blueprint about other security matters is gaining some leverage. For instance, ASEAN countries are in the same footing and demonstrate considerable commitment in providing humanitarian assistance to conflicted areas, in combatting drug and human trafficking, in addressing maritime issues like piracy, addressing transnational crimes, and in addressing disaster-related concerns. These again are ground-breaking and promising developments towards achieving and creating a politically secured ASEAN community.

Last but not the least pillar is the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC) which envisions a people-oriented and centered regional community. It wants to build a unity of nations and peoples of ASEAN by shaping a common identity and forging a shared sense of responsibility among ASEAN member states. It wants to realize the ASEAN mantra of “unity in diversity” through regional cooperation, the promotion of human and social development, respect for fundamental freedom and protection and promotion of human rights and social justice, and narrowing the development gap between and among ASEAN member states. As far as ASCC is concerned, it has achieved relative success in responding to health-related issues and concerns in the region. It also gained relative success in trying to address environmental-related concerns and improved measures in disaster preparedness and management among ASEAN countries. However, it is very slow in implementing measures for the protection and promotion of human rights and in narrowing the development gap between and among ASEAN member states. By and large, however, all these remain carved in papers, more of pronouncements than actions taken.

On the whole, ASEAN Community 2015 is a work in progress. It has to confront critical challenges as it tries to achieve its goal of a more politically cohesive, economically prosperous, and secured regional community. One such challenge lies in its continued and sustained adherence to the principles of “non-interference” and the “centrality of state sovereignty”. These two in many respects go against the principle of “collective action”, especially in responding to transnational/trans-border crimes and security concerns. This “non-interference” dogma of ASEAN needs to be revisited precisely because this runs counter to the fact that regional integration entails cross-border cooperation in resolving and addressing cross-border issues such as drug and human trafficking.

Another important consideration that needs some rethinking is the process of decision making in ASEAN. ASEAN member states decide on almost everything by consensus. But ASEAN states in many ways don’t see eye to eye on many security and human rights concerns. If “consensus” is the way to go in terms of decision making, especially in mitigating cross border issues, ASEAN will hardly be able to render decisions on cross-border issues and issues related to human rights. Hence, ASEAN should seriously reconsider and rethink the “consensus manner of voting” in many respects.

One more critical concern that ASEAN has addressed in the immediate is the seemingly lackluster enthusiasm for ASEAN Community 2015 among the general population of ASEAN countries. One reason could be the very little awareness about ASEAN Community 2015 among the peoples of ASEAN. The only sectors who have an idea of what is it all about are academics, political leaders, INGO workers, bureaucrats, technocrats, and businessmen. Other than them, the public, especially at the grassroots, does not have a hint of what ASEAN Community 2015 all about. This is quite a forlorn scenario; there is no way to build a community if people, in general, do not know exactly what is that community they are about to build. ASEAN citizens in general, especially ordinary men and women must be aware and be more educated about ASEAN Community 2015. This is a very critical concern that ASEAN member states must address if it truly wants to build a people-centered and people-oriented ASEAN.

Thus far, ASEAN Community 2015 is quite a pre-mature undertaking. Nonetheless, we cannot deny the fact that it is fast approaching. On this note, there is no other way but to embrace it positively, and try to be more strategic in how to address the negative repercussions it might bring to all parties concerned. This is the only way forward. ASEAN Community 2015 as a project does not lack vision and ideas. It has lots of these kinds of stuff. What is needed is for ASEAN to be more attentive to, and focus on the strict and fast implementation of these ideas and vision.

First published in ZamboTimes