Introduction

Article V of the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS) serves as the foundation of the Mutual Recognition Arrangements in line with the movement of skilled labor in ASEAN. It states that:

“Each Member State may recognize the education or experience obtained, requirements met, or licenses or certifications granted in another Member State, for the purpose of licensing or certification of service suppliers. Such recognition may be based upon an agreement or arrangement with the Member State concerned or may be accorded autonomously (ASEAN: 2011).”

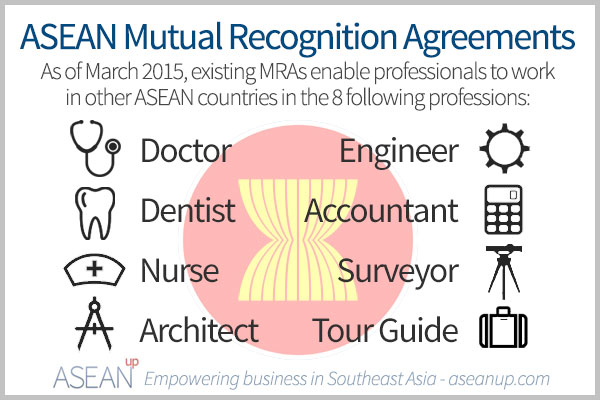

The ratification of Article V of AFAS by ASEAN’s heads of states in the 7th ASEAN Summit subsequently led to the adoption and implementation of the MRAs in seven occupational sectors (i.e., accounting, architecture, engineering, nursing, and surveying services, medical and dental practitioners, and tourism professionals). Its objective is to reduce regulatory impediments on the employment and movements of qualified and certified professionals within the ASEAN region.

The MRAs are seen as policy tools envisioned to promote greater skilled labor mobility by mutual recognition of authorization, licensing, or certification of professional services.

However, MRAs do not necessarily guarantee employment, or access of professionals to the job market in ASEAN countries as national policies of individual ASEAN country relative to the entry of foreign professionals as well as the demands and needs of the domestic labor market.

What has been achieved? Developments in the Implementation of ASEAN MRAs on Professional Services

The implementation of MRAs across the 10 ASEAN Member States (AMS) with eight occupational sectors is varied and uneven due to diverse domestic regulatory policies ad laws relative to the provisions and principles of MRAs. Hence, carrying out the provisions of the MRAs in ASEAN countries has been executed in different phases and stages.

For instance, the MRA on architecture services has been fully implemented at the regional level. Rules and procedures on the registration of foreign architects and be included in the roster of Registered Foreign Architects (RFAs) and considered as an ASEAN Architect in one’s country of origin as well as in the host country have been established. To date, there are 284 ASEAN Architect in the registry. Likewise, alternative legal schemes that allow foreign architects to practice in a host country have been instituted (e.g., temporary registration in Malaysia and special temporary permits in the Philippines). However, the movement of architects and number of ASEAN architects are relatively very low that needs further improvement (Intal: 2015).

On the other hand, regional and national implementation systems for MRA on engineering services have been in place in 2014. The system has recognized 800 foreign ASEAN Chartered Professional Engineers (ACPEs) and 1,252 Registered Foreign Chartered Professional Engineers (RFCPEs) in 2015 (Intal: 2015). Nonetheless, the numbers remain small and need to be increased.

The advancement in the implementation of MRAs on both architectural and engineering services are the most noticeable among ASEAN MRAs due to the institutionalized system of registration at the ASEAN, and presence of appropriate legal mechanisms that allow foreign professionals to practice their professions in host countries.

The tourism sector has similarly progressed. Its institutional infrastructure has been developed at the national and regional levels [e.g., National Tourism Professional Board (NTPB); ASEAN Tourism Professional Monitoring Committee (ATPMC); Tourism Professional Certification Board (TPCB)]. Although its professional registry system has yet to be completed, the training toolkits, designed to enhance the mobility of skilled tourism professionals in the region, have already been made available. The toolkits have been boosted by a web-based ASEAN Tourism Professional Registration System. This has a job-matching function that facilitates the movement of employers and professionals in the region working with the tourism industry.

For accountancy, health (i.e., nursing services, medical and dental practitioners), and surveying sectors, it has been unfortunate that no registration systems exist. Mechanisms to assess the equivalence of training and education for these professions as required by host country have yet to be adopted. In fact, most institutional mechanisms and structures for its implementation are wanting to be generated, given the huge disparities of the qualification requirements for these types of occupations across the 10 AMS.

In terms employment, out of the eight occupations currently covered by the ASEAN MRAs, seven jointly accounts for only between 0.3% and 1.4% of the total employment in ASEAN member states, while the tourism sector represents a negligible fraction of the total jobs held in ASEAN (ADB/ILO: 2014).

Indeed, beyond doubt, the implementation of the ASEAN MRAs has been dominated by gaps and ambiguities in strategies and policies. In this regard, it becomes imperative to examine the challenges and drawbacks that hinder the progress of MRAs implementation in ASEAN.

Challenges and Impediments to MRAs Implementation

The progress on MRAs implementation remains relatively very slow despite the commitment of ASEAN member states to facilitate freer movement of skilled labor under the ASEAN Economic Community. Among the challenges and impediments in the implementation of MRAs are as follows:

- The requirements and procedures for employment visas and employment passes are very challenging in most ASEAN countries. Usually, the visa application process is lengthy, there is no unified policy, and visa requirements vary across the 10 AMS. This condition limits the access of non-nationals to access employment in the host countries. For example, in Indonesia obtaining work permits for foreign workers is increasingly difficult.

- Constitutional provisions reserving jobs for nationals are another. Examples are: the imposition of caps or limitations on foreign professionals; economic and labor market tests that constrain employment of foreigners; and the requirement that foreign professionals replaced by locals within a stipulated period. In the case of Indonesia, foreigners are only allowed to hold positions that cannot be filled up by nationals. In Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar and Lao PDR, employers are obliged to ensure that there will be a transfer of knowledge to local employees, and that foreign employees will eventually be replaced by locals. The Philippines also reserves some professions for its nationals.

- ASEAN member countries have significantly varied licensing regulation, education, and testing requirements for professional recognition. For instance, a particular profession is licensed in some countries but not in others. Conversely, a person who migrated to another country will have difficulty obtaining a license for his/her profession, if she/he does not have a license from his/her country of origin.

- The reluctance of professional associations to change standards to accommodate individuals trained elsewhere or to admit foreign-trained individuals perceived to be competitors.

- Age restrictions, language requirements, cultural and religious differences.

- The lack of political will among ASEAN governments to address the above mentioned issues and concerns regarding MRAs implementation; and

- Finally, drawbacks in human, financial, technical and management interests such as:

- Lack of dedicated human resources for MRA implementation;

- Limited funding to carry out activities (i.e. information and awareness campaigns, fora, meetings, roadshows, etc.) related to the full implementation of the MRAs;

- Lack of horizontal and vertical coordination and collaboration between and among the institutions and professional groups at the national and regional levels on the details of MRA implementation; and

- Awareness of the existence, functioning, and objectives of the ASEAN Mutual Recognition Arrangements on Professional Services is lacking among professionals and employers.

Conclusion

The implementation of MRAs is indeed difficult and complex. This despondent condition requires ASEAN member states to revisit and re-examine the constraining domestic regulatory and restrictive constitutional provisions on the employment of migrant workers if ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) is to realize the objectives of MRAs. ASEAN professional bodies on the other hand, should work actively in facilitating the smooth and full implementation of the MRAs precisely because their members are its primary beneficiaries who will benefit from it in the long run. Professional education and training at national level must be strengthened further, including the proficiency in the English language to enable one to qualify for the recognition of his/her professional qualification in other ASEAN countries. All these need broad support and commitment from ASEAN governments and other stakeholders both at regional and national levels in a continuous basis, by providing resource commitments, domestic reforms on relevant domestic regulations and market demand conditions, and adjustment process for effective implementation of the MRAs.