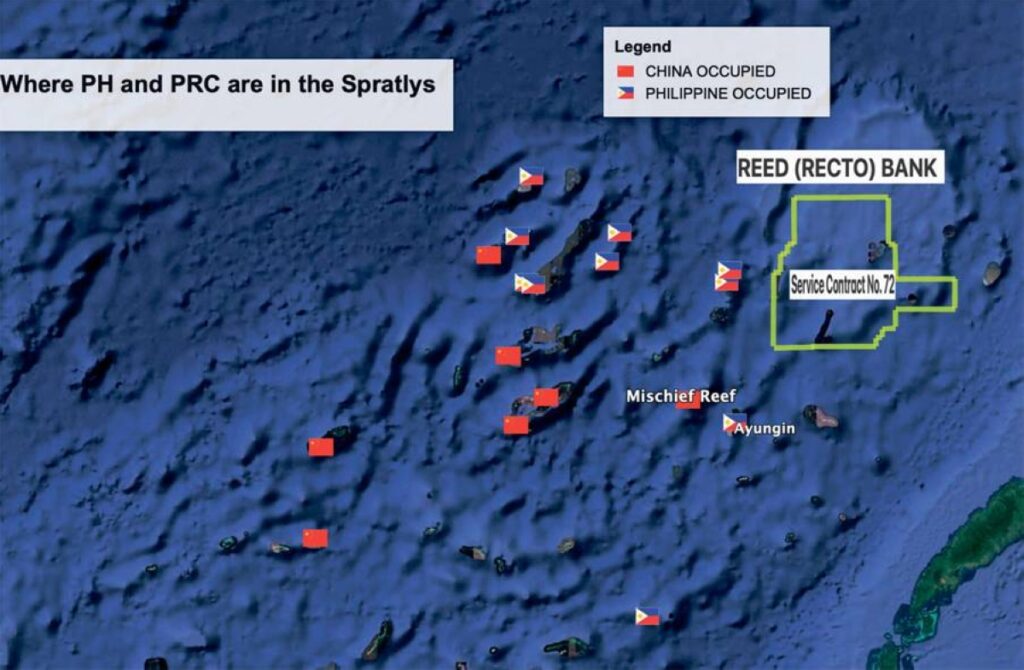

RECENTLY, territorial/maritime disputes between the Philippines and China in the South China Sea (SCS) have dominated international and local headlines. In lieu of the recent incident in the disputed SCS, particularly the area around Ayungin Shoal, where the Philippines had filed a diplomatic protest against China alleging that the China Coast Guard (CCG) vessel 5205 had directed “military-grade” laser beam and illegal radio challenges against the Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) vessel, the BRP Malapascua, on Feb. 6, 2023. The PCG spokesman for the West Philippine Sea (WPS) Commodore Jay Tarriela, in an act of “megaphone diplomacy,” said: “China continues to ignore the Philippines’ legal ownership of our EEZ over Ayungin Shoal; they continue to assert ownership of the area. Ayungin Shoal is ours.”

With all due respect to Commodore Tarriela, his latest statement is quite deceiving and misleading and does not speak of the objective reality and the facts surrounding the disputed SCS and even the status of Ayungin Shoal in relation to the United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Seas (Unclos) and even the 2016 ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA).

To say that the Philippines has “legal ownership” over our EEZ in the disputed SCS and to claim that the “Ayungin Shoal is ours” are misleading and somewhat deceptive.

Fiction vs objective reality

For the nth time, let me point out that the 2016 PCA ruling did not denote the victory of sovereignty (ownership) over the territorial and maritime claims of the Philippines in the disputed waters of the SCS precisely because the arbitral tribunal did not tackle matters related to territorial sovereignty over the disputed maritime features between the concerned parties, which further means that the tribunal did not decide who owned these maritime features, such as the Spratly Islands that are claimed by China and the Philippines and even Vietnam. It is not within the competency of the tribunal to settle sovereignty issues in the same manner that Unclos is not the right or viable international law instrument that could be used to resolve sovereign territorial disputes among and between countries. Unclos does not apply to sovereignty disputes or disputes over how to delimit maritime zones. The resolution of these types of disputes is left to the parties concerned to resolve among themselves.

Hence, the tribunal did not delimit (demarcate or set limits) any maritime boundaries between the Philippines and China in the SCS. The award simply clarified the maritime entitlements of the Philippines in the WPS, declared the nine-dash line of China as being without basis, acknowledged the damage to the marine ecosystem and resources caused by reclamation activities in the SCS, and even ruled the surrounding waters of the Scarborough Shoal as traditional fishing grounds where Filipinos, Chinese and even Vietnamese could fish. It also stated that the shoal is a rock that cannot generate an EEZ because it cannot sustain life, which even weakens the claim of the Philippines.

Furthermore, although the Second Thomas Shoal in the Spratly islands (Ayungin Shoal to the Philippines or Rén’ài Jiāo in Mandarin Chinese) is located 105 nautical miles west of Palawan and sits within 200 nautical miles of the Philippine coast and, based on Unclos would be part of the EEZ and continental shelf of the Philippines, which means the Philippines has sovereign rights, the arbitral tribunal declined to takeup the issue concerning the shoal because it was a military matter and thus beyond the purview or scope of Unclos. The Philippine military currently occupies the shoal.

On the other hand, having “sovereign rights” over our EEZ in the disputed SCS does not mean we have sovereignty or ownership over the area. It only means we have jurisdiction to exploit the marine or natural resources in our EEZ below the sea. The area above our EEZ is already international waters. And mind you, jurisdiction is not synonymous or tantamount to ownership. Sovereignty and sovereign rights are two different things.

Based on Unclos, sovereignty bestows full rights, ownership or supreme authority, on a country within its territorial waters, which stretch to 12 nautical miles from the shore. While sovereign rights in an EEZ based on Unclos extends to 200 nautical miles from a country’s shores, much further out to sea, “no longer concerns all of a State’s activities, but only some of them.” Part V, Article 56, Section 2 of Unclos even stipulates that, “In exercising its rights and performing its duties under this Convention in the exclusive economic zone, the coastal State shall have due regard to the rights and duties of other States and shall act in a manner compatible with the provisions of this Convention.”

Another reality that we also need to contend with is the fact that China did not participate in the arbitration process and did not recognize the PCA ruling. Also, the PCA ruling is precisely akin to a “paper tiger” because there’s no enforcement mechanism. In an anarchic and “survival of the fittest” international state system, where the world lacks any supreme authority or sovereign, meaning there is no world police force, the PCA ruling is a “paper tiger,” which appears to be powerful or threatening, but is ineffectual. Bluntly speaking, it is somehow challenging and difficult to enforce. This is the glaring reality.

The only way to enforce the PCA ruling without the concession of China, if the Philippines insists, is to go to war with China, which is unthinkable for any Filipino who is rational, wise and pragmatic enough to consider the ramifications and impact of a military confrontation with China, which could be fatal and devastating for the country. In this regard, we must ask ourselves, at what cost, at whose expense, and who would ultimately benefit if China and the Philippines end up in a military conflict over rocks, fish or shoals?

Conclusion

We must consider and keep in mind all these realities surrounding the complex, sensitive and delicate situation of the disputed SCS so we know exactly where we stand in our claims over the contested waters. Turning a blind eye to these realities is tantamount to asserting our claim devoid of proper direction or guidance, solid legal grounding, and pragmatic considerations, which would be to our disadvantage and may lead us astray as a country.

Indeed, to fight for what is truly ours is a commendable spirit of nationalism and patriotism. Nevertheless, rousing and prompting Filipinos to fight for something wholly based on deception and misinformation is idiocy and a disservice to the Filipino people. As a Filipino, I believe that we need to assert our sovereignty and rightful claims on issues that have something to do with preserving our territorial integrity and core national interests as a sovereign state. But in doing so, we should fight a good fight based on facts and ground realities because doing otherwise based on deception and misinformation would be akin to fooling ourselves.

The Philippines and China are geographical neighbors, which will probably never change over time. Despite being neighbors and friends, the two countries have conflicts of interest and differences, like any kind of relationship. But what matters is the maturity and constructive way of resolving these differences.

To avoid further and untimely skirmishes among and between claimant states of the disputed SCS, the Philippines, China and the Asean member-states should work hard toward adopting and concluding the Code of Conduct (COC) for the South China Sea. Though the COC is not a mechanism to settle sovereignty disputes, it will provide rules and guidance on proper conduct at sea among claimant states to avoid unfortunate incidents and unthinkable military confrontations in the SCS.

Source: The Manila Times

https://www.manilatimes.net/2023/03/02/opinion/columns/theres-more-to-recent-ayungin-shoal-incident-than-meets-the-eye/1880907