One of the most crucial and pressing issues related to children in the Philippines is the issue of children in armed conflict. Children in situations of armed conflict (CSAC), including Children Involvement in Armed Conflict (CIAC), are among the most vulnerable groups of children, often falling victim or becoming targets for harm and violence.

Children involved in armed conflict are still very much prevalent in the Philippines especially in war-prone and war-torn areas of SOCCSKSARGEN and Mindanao. SOCCSKSARGEN is an administrative region of the Philippines located in South-Central Mindanao. It stands for the region’s four provinces and two cities, namely, South Cotabato, Cotabato City, Cotabato Province, Sultan Kudarat, Sarangani, and General Santos City.

Likewise, children’s involvement and their precarious situation in armed conflict are also prevailing in certain areas of Luzon and the Visayas where intensified counter-insurgency operations of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) against the New Peoples’ Army (NPA) of the Community Party of the Philippines (CPP) are on-going. Just to note, the CPP is the longest-running insurgent group in the world thus far. It has waged a “protracted-war” or “armed struggle” for more than 50 years since its founding in 1969.

However, its decriers typify its “protracted-war” as lawlessness and violence. Its military arm is the New People’s Army (NPA), and its political arm is the National Democratic Front (NDF). The CPP-NDF-NPA since the beginning has been keen on overthrowing the government of the Philippines but had never politically or militarily for that matter controlled any province or even a single city in its 52 years of existence. Their military bases are in the forests and mountains across the country.

Children in armed conflict situations experience various forms of violations and abuse, which include: (a) becoming internally displaced persons in their own country; (b) being killed and maimed in crossfires, which include targeted shootings, crossfire, airstrikes, shelling, indiscriminate attacks, summary executions, unexploded ordnance, and/or mistreatment during detention; (c) the use of schools especially those located in interior areas as military camps which result in harassment of teachers and students (d) abduction; (e) rape and other gender-based violence; (f) the denial of humanitarian services in remote areas controlled by non-state armed groups; and (g) the precarious and continuous recruitment as soldiers/combatants by various insurgent and terrorist groups in the country.

Backdrop

Article 38/3 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), states parties are prohibited from recruiting any person who has not attained the age of 15 years into the armed forces. Likewise, even in recruiting among those persons who have attained the age of 15 years but who have not attained the age of 18 years, states and non-state armed groups shall endeavour to give priority to those who are oldest.

The Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict sets 18 as the minimum age for direct participation in hostilities, for recruitment into armed groups, and compulsory recruitment by governments.

Nevertheless, the recruitment of children as combatants by non-state armed groups in the Philippines continues despite the prohibitions set by the UNCRC and its Optional Protocols.

This has been evidenced by the recent reports and statements of UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General, Virginia Gamba, and UN Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons, Maria Grazia Giammarinaro during the 44th UN Human Rights Council Session, who both expressed and drew attention to the situation of children in the Philippines being recruited for armed combat.

UN Special Representative Gamba outlined the challenges in ending and preventing grave violations against children including their recruitment and use; killing and maiming; abduction; rape and sexual violence, while UN Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons, Giammarinaro, highlighted how conflict and post-conflict settings heighten the vulnerability of children to being trafficked to serve as soldiers, servants, or sexual slaves.

On 6 July 2020, the Philippine Permanent Representative to the United Nations (UN), Ambassador Evan P Garcia, conveyed the Philippines’ full support to the UN’s experts work and urged them to continue paying close attention to the “modus operandi” through which the recruitment of child soldiers is carried out in different settings in the Philippines.

Garcia encouraged the UN experts to further intensify their work in the area of combating the recruitment of child soldiers in the Philippines. He highlighted the employment by certain terrorist organisations and armed non-state actors like the CPP-NDF-NPA, which according to him, exploited the cover of charitable schools and school-based youth organisations, to train child combatants for their terroristic activities, and insidiously recruit child combatants, taking them away from the safety of their families, schools, and communities.

He said, “the terrorist group abuses the cover of ‘human rights defender’ to escape detection, project legitimacy, solicit funds from unwitting foreign donors, and evade accountability while victimising thousands of vulnerable children, especially those from indigenous communities.”

Hence, the recruitment of child soldiers by non-state armed groups is still a persistent and prevailing problem in the Philippines.

Recruitment And Repercussions

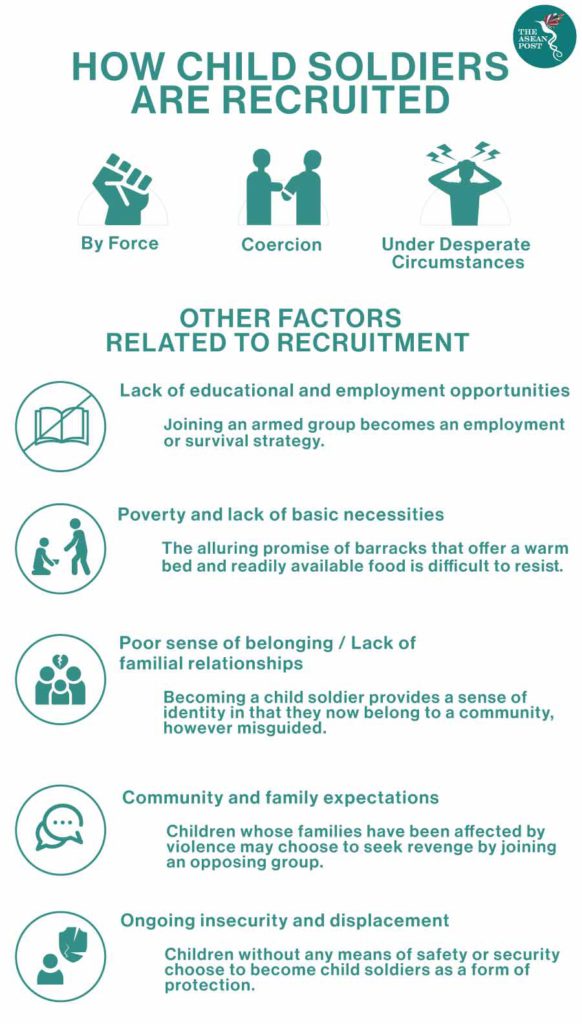

The recruitment of children as combatants in the Philippines can be attributed to several factors including: (a) joining the ranks because of psychological reasons like thrill and excitement; (b) social tension like peer pressure; (c) because of propaganda of some non-state actors; and (d) forced recruitment or abduction.

Most often than not, non-state armed groups target the emotional, psychological, mental, or physical vulnerabilities of children, as well as the situations in their families and communities.

These young combatants participate in all aspects of contemporary warfare. They wield arms/weapons on the front lines of combat, serve as human mine detectors; participate in suicide missions; carry supplies; act as spies, messenger decoys, or lookouts; courier or guards; undergo training, drill, or other preparations; logistics and support functions; portering, cooking and domestic labour. Some of them, especially girls/young women are subjected to rape, and various forms of sexual slavery, and even forced marriage.

Due to the involvement of these children in conflict, some if not many of them, generally end up with physical disabilities, while others die in military encounters and confrontations. Many of them suffer mental, emotional, and physical exhaustion. This is because their bodies cannot accommodate or bear the load of activities needed to fulfil the requisites and regiment of military/combat training.

Their involvement in armed conflict as child soldiers not only separates them from their families and makes their lives miserable, but most importantly, traumatises them (i.e. mental disturbance and morbidity), makes them uneducated and illiterate, instils extreme fear in them, and fundamentally destroys their bright futures.

Standpoint

Indeed, one of the alarming trends relating to children in armed conflict, and children in the Philippines in general, is the recruitment and existence of child combatants. These child soldiers are between 10 and 18 years old. They wear combat uniforms and carry weapons, but by whatever standard, they are still children. For what it may seem, they are being used to play war games by certain insurgent and terrorist elements of Philippine society instead of being cared for in the comforts of their homes, surrounded by their families, and communities. Hence, these child soldiers need the utmost protection and attention of the Philippine government.

In this regard, laws, programs, and advocacies pertinent to the issue of child soldiers, and their meaningful implementation should be intensified and given due priority, attention, and resources. For instance, the passage into law and the meaningful implementation of the Republic Act 11188, or the “Special Protection of Children in Situations of Armed Conflict Act,” signed on 10 January 2019, is thus far a welcomed development. The law is an important measure toward improving the protection of children and ensuring accountability for grave violations.

The law declares children as “zones of peace,” aimed at protecting children in situations of armed conflict from all forms of abuse and violence and prosecute persons or groups violating the measure. The new law is part of the Philippines’ compliance with international obligations including the UN CRC, particularly the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Convention Against Torture, and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and various UN Security Council resolutions related to children affected by armed conflict.

Likewise, it is also crucial that pertinent interventions and measures be put in place and into action to address the security and well-being of children involved in armed conflict. These child combatants must be disarmed, demobilised, and socially reintegrated back into their respective communities, families, and civilian life.

When demobilised and disarmed, they should be provided with pertinent and necessary socio-economic and psycho-social interventions and measures to address their security and well-being needs, to help them cope up with life outside of soldiering, and to help them assimilate once again into normal civilian life.

Examples of interventions are education and vocational training, the provision of psychosocial support like peer-to-peer support, community-based support, and psychosocial counselling. A protective environment for demobilised child soldiers must be ensured as well to prevent them from being re-recruited and to have a more stable life.

Conclusion

Child soldiering regardless of reasons and justification, and whether voluntarily or involuntarily, is at the end of the day, without doubt, a serious offense against children and a grave abuse of human rights. Hence, the Philippine government must continue to put forward efforts in ending and preventing the engagement of children in warfare and their recruitment at all cost and by all means.

Source: The ASEAN Post

https://theaseanpost.com/article/will-child-soldier-recruitment-ever-end