The Duterte administration’s “war against illegal drugs” thus far is one among many controversial issues that has received a great deal of media attention both, locally and internationally and has earned extra attention in foreign policy circles and among local and international human rights organisations.

The elimination of the drug problem in the country is one of Duterte’s campaign promises from the 2016 national elections. He promised to eliminate the problem of illegal drugs in the country in around six months. However, along the course of his administration, Duterte had come to realise and has acknowledged the fact that the country has a long way to go in addressing this deep-seated societal menace because of its enormity and sheer magnitude more so amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

He expressed such sentiment in his “Fifth State of the Nation Address (SONA)” on 27 July, 2020 where he said, “The dealers and purveyors of illegal drugs, hiding in the shadow of COVID- 19, have stepped up their activities. The amount of shabu valued at millions of pesos seized during police operations speak volumes of the enormity and weight of the problem that we bear”.

Nonetheless, even amid the pandemic, Duterte pledged to continue the fight against illegal drugs in the country until his term ends with more intensified efforts to secure and protect the country most especially the youth from the scourge of illegal drugs.

Landscape And Context

In 1972, the drug problem was just at its incipient stage, with only 20,000 drug users. After a decade, in 1982, the number of “methamphetamine hydrochloride” or locally known as “shabu” users in the country had increased significantly. There was a radical shift in the illegal drug landscape in the 1990s.

It was during this time that the illegal drug problem in the country worsened both, in terms of the scope of illegal operations and its breadth. By the late 1990s, the Philippines had become a net producer and exporter of “shabu” or “poor man’s cocaine.”

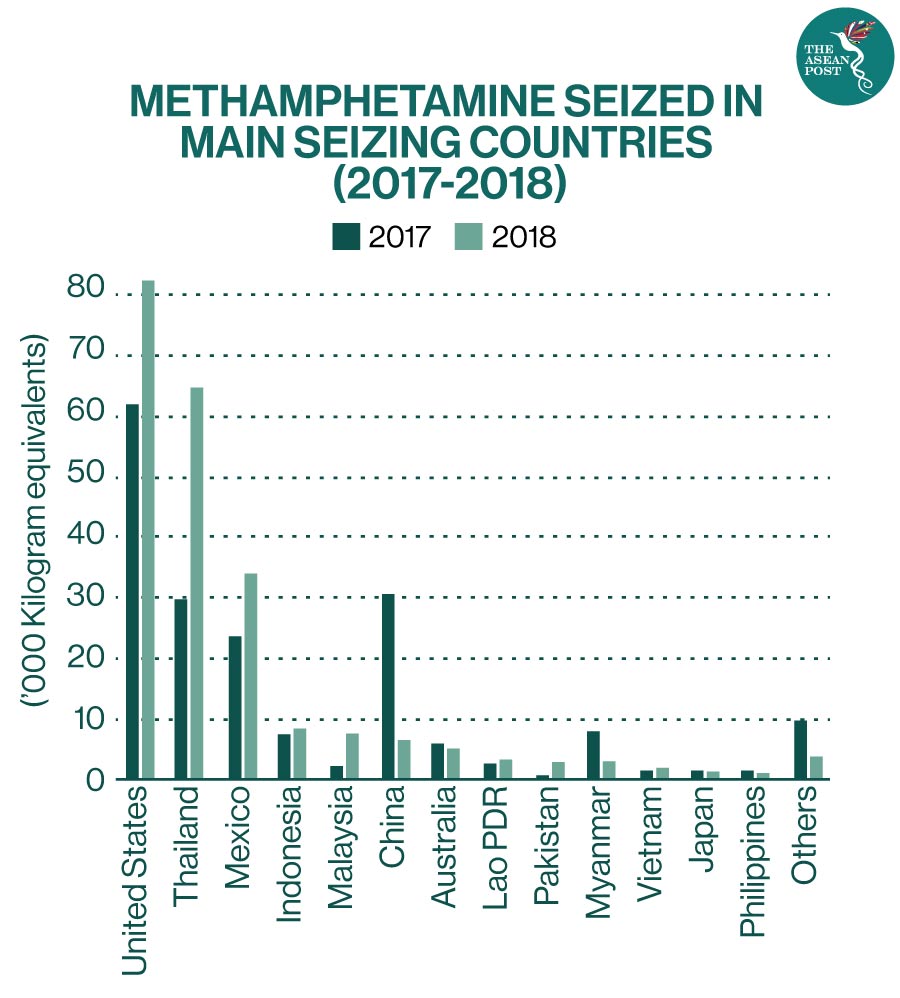

Subsequently, in 2003, the Philippines was said to have around 1.8 million drug users, which is equivalent to 2.2 percent of the population based on the 2003 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report. By 2012, the United Nations (UN) said the Philippines had the highest rate of “methamphetamine” or “shabu” abuse among countries in East Asia, and about 2.2 percent of Filipinos between the ages of 16 and 64 years were methamphetamines users.

The “2015 Nationwide Survey on the Nature and Extent of Drug Abuse in the Philippines” commissioned by the Philippine Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB), and carried out by the “Resources, Environment and Economic Centre for Studies, Inc. (REECS), which was released in 2016, had estimated that the drug market in the country was valued at around PHP 55.8 billion (US$1.1 billion) per one-year consumption or 16,138 kilogrammes in weight. To note, the DDB is the government agency mandated to formulate policies on illegal drugs in the Philippines.

Likewise, the study reported that the country had around 1.8 million “current users” of illegal drugs and 4.8 million “lifetime users” (those who have used drugs at least once in their lifetime). The study also purported that, in Metro Manila alone, 99 percent of barangays had at least one drug user-resident, and the prevalence of families having a drug-using member was 2.6 percent, which is quite alarming.

It was also observed that there was an increasing trend in the use and abuse of illegal drugs in the country from 2010 to 2015. Based on data from the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA), there was a significant increase in the incidence of drug abuse based on the number of persons arrested due to drug abuse. For instance, in 2010, there were 174 persons arrested due to illegal drugs; 261 in 2011; 223 in 2012; 384 in 2013; 393 in 2014; and 955 in 2015.

Also, data from the Philippine National Police (PNP) showed a high increase in the incidence of drug abuse through the total number of arrested persons, referring to both dangerous drug traffickers and users from 2011 to 2015. For instance, there was an almost 900 percent increase in the incidence of illegal drug related problems in the country, from 5,002 arrests in 2011 to 44,453 arrests in 2015. And in 2016, the UN Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reported that 1.1 percent of Filipinos aged 10 to 69 used “methamphetamine hydrochloride” or “shabu,” and most of the barangays of the greater Metro Manila areas were affected by illegal drugs.

Hence, this data and information are indeed indicative that dangerous drug use and trafficking in the Philippines has indeed increased tremendously over time. The illegal drug problem in the Philippines has reached epidemic proportions and hence became one of the top priorities of the Duterte administration.

Silver Linings

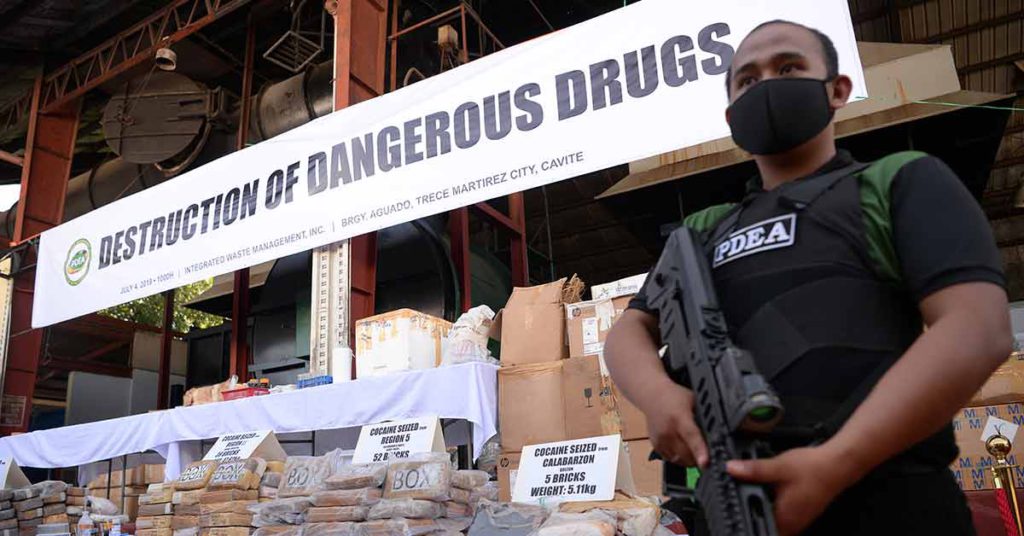

During the past four years of the Duterte administration, the fight against illegal drugs to a considerable extent has gained traction and made significant headway. Based on data and statistics from the PDEA, the “Anti-Illegal Drugs Operations” of the government from 1 July, 2016 to 31 July, 2020, thus far, have generated significant and critical results.

One of the relative successes in the fight against illegal drugs is the 1.4 million individuals who voluntarily surrendered and are now continuing with their drug rehabilitation and treatment. Many if not all of them were admitted to the 965 “Balay-Silangan Reformation Centers” and 15 “Treatment and Rehabilitation Centers” established by PDEA across the country.

3,254 children were rescued from their involvement in illegal drug activities of which around 1,817 were pushers, 868 were possessors, 385 were users, and 161 were drug den visitors. Likewise, out of 42,042 “barangays” (villages) across the country, around 19,876 were proclaimed as “drug cleared barangays,” while 14,491 barangays are yet to be cleared from illegal drugs.

The total value of illegal drugs seized, amounted to PHP 52.77 billion (US$1.08 billion). Law enforcers were also able to dismantle 581 illegal drug dens and 16 clandestine laboratories. The number of anti-illegal drug operations including those conducted during the first half of 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic by the PDEA with other law enforcement agencies was 173,343.

In these anti-illegal drug operations, around 251,889 individuals were arrested, of which around 9,706 were “high-value targets” comprising of: (a) 279 foreign nationals; (b) 336 elected officials; (c) 96 uniformed personnel; (d) 40 government employees; (e) 2,835 listed target individuals; (f) 741 drug group leaders/members; (g) 62 armed group members; (h) 947 drug den maintainers; (i) 222 individuals on the wanted list; and (j) 11 celebrities/prominent personalities. 3,776 individuals were also arrested during “high-impact anti-illegal drug operations”.

Unfortunately, there were casualties and fatalities in the “war against illegal drugs” in the Philippines. To note, around 5,810 individuals died. Nonetheless, the PNP is addressing the deaths of drug suspects during anti-illegal drug operations by conducting “motu proprio” or “automatic investigations” on these deaths.

This is to ensure that erring policemen will not get away with any wrongdoings. Thus, out of the 4,708 “motu proprio” investigations conducted by the PNP for the period from July 2016 to May 2019, 72 percent or 3,401 cases were forwarded to the PNP Chief for the imposition of recommended disciplinary action.

The Philippine government also instituted “Barangay Anti-Drug Abuse Councils” or BADACs to assist law enforcement agencies in illegal drug clearing operations at the barangay level. BADACs are also tasked to implement programs and projects like information campaigns in their communities that are geared toward discouraging the youth from engaging in illegal drugs. In 2018, 99.95 percent or 42,024 of the 42,045 barangays nationwide had organised their BADACs already.

Differing Perspectives

In as much as the infamous “fight against illegal drugs” of the Duterte administration has made considerable progress and traction, it is thus far one of the most controversial issues, spawning contrasting opinions among Filipinos.

To his detractors and critics, Duterte’s approach in exterminating illicit drugs in the country is not only inhumane and misguided but has inflicted damage and negative consequences on the human rights situation of the country. For most of his critics, the loss of lives is the most appalling and instantaneous outcome of the “drug war.”

Duterte’s political critics claim that the government’s policy and approach in combating illegal drugs are not compliant to human rights standards most particularly the provisions concerning the presumption of innocence and adherence to due process as enshrined in the 1987 Philippine Constitution and in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), of which the Philippines is a signatory.

But for Duterte, the “fight against illegal drugs” is a matter of public interest and public order. Duterte has contended several times that his concern is not just “human rights” but “human lives,” which according to him is safeguarding Filipinos especially the youth from the scourge of illegal drugs.

For Duterte’s supporters on the other hand, who thus far outnumber his critics, Duterte is a faithful public servant who is just doing what is good for the country. They regard him as a good and decisive leader defending the country from ruthless criminals, from drug lords, and the many evils of illegal drugs.

Many if not all of Duterte’s supporters argue that, though the “fight against illegal drugs” sadly may have claimed lives, nevertheless it saved and is continuously saving millions of lives most notably those of the younger generation who are highly vulnerable to illegal drug use.

Many of his supporters believe that “inflicting violence”, “intentional killings” or “extra-judicial killings (EJKs)” is not and has never been the policy of the Duterte administration. These are mere allegations by his political detractors and critics devoid of concrete evidence.

Conclusion

Given the magnitude of the drug problem in the Philippines, the fight against illegal drugs under the Duterte administration and even beyond is thus far imperative and necessary.

However, since the drug problem in the Philippines is multi-dimensional, deeply seated in the structural causes of poverty, inequality, and powerlessness of the Filipino people, the Philippine government must ensure a more comprehensive and holistic approach and should not just treat the problem of illegal drugs as a problem of criminality and public order, but rather should also pay more attention and focus on preventive measures, treatment, rehabilitation, and the re-socialisation of drug-abusers.

In the fight against illegal drugs, the government should also continue to pursue a multi-sectoral partnership between the government, communities at the barangay level, the media, church, and civil society to ensure its effectiveness.

Continuous reassessment of the strategies and approaches in the fight against illegal drugs is also a necessary thing for the government to do to determine what are the approaches and strategies that are working and what are those that need to be changed.

Source: The ASEAN Post

https://theaseanpost.com/article/war-against-illegal-drugs-amid-pandemic